You may know that probiotic are live microbes that, when taken in sufficient amounts, provide health benefits to the body. However, with so many options out there – how do you decide which one to choose? Well, that depends on what you want the little bugs to do for you. Whilst a Hyundai and a Ferrari are both cars, you know which one you’d pick for fuel economy and which one would win a race. The same story applies with probiotics – whilst many may be beneficial, each strain carries out different actions, so it’s super important to choose the right one for your specific needs.

Probiotics primarily exert their health benefits by influencing the trillions of organisms that exist within your gut, collectively known as your intestinal microbiome. Hot in scientific circles right now, there are many biological processes your microbiome is purported to influence, including:

- Local and systemic immunity, preventing infection and the requirement for medications (such as antibiotics);[1],[2],[3],[4]

- Immune system regulation, reducing the risk of allergies or autoimmune conditions;[5],[6]

- Preventing the colonisation of pathogenic organisms, protecting you from gastrointestinal infections;[7]

- Appetite regulation, to prevent overeating and weight gain;[8],[9] and

- The production of brain chemicals that may help support a healthy mood[10],[11] (more on the mind-gut connection here).

It’s important to bear in mind that not every probiotic is going to achieve everything mentioned above.

Probiotic functions are ‘strain specific’ and cannot be generalised to probiotics in general.

To read more about the importance of strain specificity with probiotics, read this blog here.

Offsetting the Disruptive Effects of Antibiotics

One crucial strength of probiotics is their capacity to protect the gut microbiome from disruption when taking antibiotics.[12],[13] Recently, an Israeli study refuting this effect made headlines around the world, despite well-established evidence to the contrary. Whilst there were several issues with the study itself, there were also important inaccuracies that were unfortunately disseminated by the mainstream media about the overall findings of the study. To take a closer look at this research, and for a summary of the evidence that supports the use of strain-specific probiotics to restore the microbiome following antibiotic therapy, click here.

With November 12th to 18th being Antibiotic Awareness Week, as declared by the World Health Organization (WHO), this is also the perfect time to discuss what specifically can be done to minimise any negative effects that may accompany antibiotic administration. For example, one of the most common yet unwanted side effects is antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD), which in adults is estimated to affect up to 70% of the population.[14] Furthermore, the WHO also has a pretty dire warning about the dangers of antibiotic resistance (see here), something we should all be conscious of when discussing antibiotic use with our GPs.

Be Informed and Choose What Works

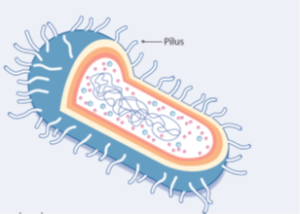

That said, antibiotics have their place in specific circumstances so the question is how and what to use to minimise the disruption they can cause to the gut microbiome. With the evidence clear on the benefits of taking probiotics alongside antibiotics,[15],[16],[17] one that particularly shines in this situation is Lactobacillus rhamnosus (LGG®). LGG® is the world’s most researched probiotic,[18] and has been shown to effective in preventing AAD in both children and adults,[19] as it markedly strengthens the important core bacterial species within your gut that keep the entire gut environment healthy.[20],[21],[22],[23] Whilst there are a number of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG products on the market, speak to your Practitioner about sourcing authentic LGG®. Only authentic trademarked LGG® will reliably have the unique hair-like appendages (see Figure 1) that increase its adhesion to the mucus membranes lining the gut – it is this feature that allows it to exert its positive health benefits.[24]

Figure 1: LGG® with pili (hair-like appendages) to maximise mucosal adhesion.

Further, a 2016 review of probiotics found LGG® and the beneficial yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (boulardii) or ‘SB’, both reduce the risk of AAD, potentially reducing the need for antibiotics to treat secondary infections. The review went on to say that through this mechanism (and thus the reduction in likelihood that you will experience unpleasant adverse gut effects),

probiotics contribute to better adherence to antibiotic prescriptions, and thereby reduce the evolution of antibiotic resistance.[25]

To fully discover the benefits of probiotics speak to your natural healthcare Practitioner. They are best equipped to advise which strain specific probiotics can optimally support your gut microbiome to achieve gastrointestinal balance, especially if you have taken antibiotics recently. To find an appropriately qualified Practitioner in your area, click here.

[1] Ohland CL, MacNaughton WK. Probiotic bacteria and intestinal epithelial barrier function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010 Mar 18;298(6):G807-19.

[2] Szajewska H, Kołodziej M. Systematic review with meta‐analysis: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in the prevention of antibiotic‐associated diarrhoea in children and adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Nov;42(10):1149-57.

[3] Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 15;375(24):2369-79.

[4] Ohland CL, MacNaughton WK. Probiotic bacteria and intestinal epithelial barrier function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010 Mar 18;298(6):G807-19.

[5] Claus SP, Guillou H, Ellero-Simatos S. The gut microbiota: a major player in the toxicity of environmental pollutants? NPJ Biofilms and Microbiomes. 2016 May 4;2:16003.

[6] Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 15;375(24):2369-79.

[7] Ohland CL, MacNaughton WK. Probiotic bacteria and intestinal epithelial barrier function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010 Mar 18;298(6):G807-19.

[8] Mazzoli R, Pessione E. The neuro-endocrinological role of microbial glutamate and GABA signaling. Front Microbiol. 2016 Nov 30;7:1934.

[9] Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 15;375(24):2369-79.

[10] Mazzoli R, Pessione E. The neuro-endocrinological role of microbial glutamate and GABA signaling. Front Microbiol. 2016 Nov 30;7:1934.

[11] Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 15;375(24):2369-79.

[12] Moré MI, Swidsinski A. Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 supports regeneration of the intestinal microbiota after diarrheic dysbiosis–a review. Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology. 2015;8:237.

[13] Eloe-Fadrosh EA, Brady A, Crabtree J, Drabek EF, Ma B, Mahurkar A, et al. Functional dynamics of the gut microbiome in elderly people during probiotic consumption. MBio. 2015 May 1;6(2):e00231-15.

[14] Szajewska H, Kołodziej M. Systematic review with meta‐analysis: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in the prevention of antibiotic‐associated diarrhoea in children and adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Nov;42(10):1149-57.

[15] Szajewska H, Kołodziej M. Systematic review with meta‐analysis: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in the prevention of antibiotic‐associated diarrhoea in children and adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Nov;42(10):1149-57.

[16] Ouwehand AC, Forssten S, Hibberd AA, Lyra A, Stahl B. Probiotic approach to prevent antibiotic resistance. Ann Med. 2016 May 18;48(4):246-55.

[17] Jungersen M, Wind A, Johansen E, Christensen JE, Stuer-Lauridsen B, Eskesen D. The science behind the probiotic strain Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BB-12®. Microorganisms. 2014 Mar 28;2(2):92-110.

[18] Segers ME, Lebeer S. Towards a better understanding of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG-host interactions. Microbial Cell Factories. 2014 Aug 29;13 Suppl:S7. Doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-13-S1-S7.

[19] Szajewska H, Kołodziej M. Systematic review with meta‐analysis: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in the prevention of antibiotic‐associated diarrhoea in children and adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Nov;42(10):1149-57.

[20] Eloe-Fadrosh EA, Brady A, Crabtree J, Drabek EF, Ma B, Mahurkar A, et al. Functional dynamics of the gut microbiome in elderly people during probiotic consumption. MBio. 2015 May 1;6(2):e00231-15.

[21] Canani RB, Sangwan N, Stefka AT, Nocerino R, Paparo L, Aitoro R, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG-supplemented formula expands butyrate-producing bacterial strains in food allergic infants. The ISME journal. 2016 Mar;10(3):742.

[22] Korpela K, Salonen A, Virta LJ, Kumpu M, Kekkonen RA, De Vos WM. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG intake modifies preschool children’s intestinal microbiota, alleviates penicillin-associated changes, and reduces antibiotic use. PloS One. 2016 Apr 25;11(4):e0154012.

[23] Bajaj JS, Heuman DM, Hylemon PB, Sanyal AJ, Puri P, Sterling RK, et al. Randomised clinical trial: Lactobacillus GG modulates gut microbiome, metabolome and endotoxemia in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014 May;39(10):1113-25.

[24] Segers ME, Lebeer S. Towards a better understanding of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG-host interactions. Microbial Cell Factories. 2014 Aug 29;13 Suppl:S7. Doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-13-S1-S7.

[25] Ouwehand AC, Forssten S, Hibberd AA, Lyra A, Stahl B. Probiotic approach to prevent antibiotic resistance. Ann Med. 2016 May 18;48(4):246-55.

Leave a Comment