More people are paying close attention to the food they eat; reading labels with eagle eyes and looking for the term ‘organic’, but is the desire for organic produce just driven by clever marketing? What is it about knowing food is organic that buyers feel gives them a health advantage? And is buying organic worth the price tag?

If you look up a definition of ‘organic farming’ it refers to food produced without the use of chemical fertilisers, pesticides, or any other artificial chemicals. That’s the real reason that many consumers choose to invest in organic – because they are choosing to avoid the chemical cocktail that ‘conventionally’ grown produce comes with – namely pesticides and fertilisers.

According to Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ), chemical residues on foods have a maximum limit to be legally sold; a limit that applies for both imported and locally grown produce.[1] However, for organic food advocates – any chemical contamination is too much, and they are prepared to pay for what they consider to be cleaner, safer options.

If Agricultural Chemicals Were Toxic, No One Would Allow Their Use, Right?

Here’s the thing – a number of researchers have been investigating this very question, and others, with sobering results. You see, while many of these agricultural chemicals were tested once upon a time and considered ‘non-toxic’, because they’d be used at levels far below a toxic dose (so they must be safe); however, no one at that time was measuring how really tiny amounts of the same chemicals might disrupt our delicate hormonal system. Nor was anyone looking at what the effect would be if you mix up miniscule amounts of a number of these same chemicals into the equivalent of the aforementioned ‘chemical cocktail’ – how might that impact human health over months or years, or the next generation, or the next? And could really subtle effects of these same chemicals occur before we are even born, impacting how our cells might function in years to come? How vulnerable are our developing children? These questions and more are beginning to be answered – and the results are not promising.

In a nutshell, many of the chemicals used in agriculture are now termed the somewhat ominous ‘endocrine disrupting chemicals’ or EDCs. These are unfortunately ubiquitous in our environment now, and many considered ‘persistent organic pollutants’ or POPs, meaning they don’t break down and disappear but remain in the environment whether we like it or not. High levels of these EDCs in women have been linked to abnormal puberty, irregular menstrual cycles, reduced fertility (or infertility), polycystic ovarian syndrome, endometriosis and fibroids.[2] Read this blog for more about EDCs. Nevertheless, the point remains that we simply don’t know yet what all the long-term effects are, and this makes many people choose to do what they can now, rather than wait – one of these choices is to eat organically to try to limit their chemical exposure.

What to Look for When Buying Organic

In Australia there are currently seven organic certifiers accredited by the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (DAFF). There is also the Organic Growers of Australia (OGA), who are accredited by the International Organic Accreditation Service rather than DAFF. However OGA will no longer be certifying from 30th June 2018, with producers requested to transition over to Australian Certified Organic instead. As there may still be some OGA certified products available for a short while, their logo has been included in Figure 1.

According to the National Association for Sustainable Agriculture, Australia (NASAA) it is important to look for ‘certified organic’ on labels[3] as the term organic isn’t actually protected and many companies leverage the terms ‘natural, green’ and/or ‘organic’ to catch consumers eyes and entice them to buy – so it’s wise to be a little suspicious.

Look for the term ‘certified organic’ on your items, as this can only be used by those who are actually producing what you are really looking for.

Figure 1: Don’t Be Fooled – Authentic Organic Produce Has to be Certified and Will Display One of These Certification Logos.

What If You Cannot Afford to Go All Organic?

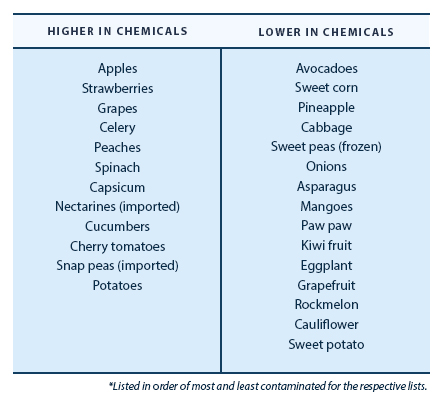

It’s true that going organic has a cost (some say it’s the true cost of food production) so if you cannot stretch to going all organic – you can still make some smarter choices based on those foods likely to contain higher levels of chemicals than others (see Table 1). You can also wash conventionally grown produce as soon as you purchase it. Not only can this help remove waxes (if you use a brush on these foods) and pesticide residues, but could reduce bacterial contamination also so it’s a good idea anyway. Washing does make a difference, with a US study carried out over three years demonstrating that simply rinsing under tap water for 30 seconds significantly reduced 9 out of 12 pesticides.[4]

Table 1: Fruits and Vegetables That are Higher and Lower in Chemicals.

Other tips are to buy from local organic farmers markets, buy seasonally when prices are more likely to be comparable to conventional produce; and look into organic food box schemes – these connect local organic farmers with customers direct; cutting out the ‘middle man’ and therefore keeping prices lower.

Does Going Organic Make a Difference?

Actually yes.

Researchers have demonstrated that following an organic diet reduces chemical load, and fast, with an Australian study showing organophosphate pesticide levels decreased by 89% within only seven days in adults following an organic diet (compared to eating conventionally grown food over the same timeframe).[5]

But it’s more than avoiding the pesticides; organic foods are typically also not made with synthetic colourings, preservatives, additives or genetically modified ingredients,[6] so there is a bigger picture.

Don’t Forget to Detox

Another proactive step in reducing any toxic burden you may have built up is to carry out a clinical detoxification program; but don’t buy ‘off the shelf’ – speak to your healthcare Practitioner who can assess your particular needs and who can recommend a program that will support all detoxification pathways, particularly your liver, gut and kidneys. Many of the ingredients used in Practitioner guided detox programs are potent antioxidants, such as green tea, milk thistle, turmeric and spirulina. Depending on your situation, you may also benefit from using certain phytonutrients ongoing to help improve your resilience against many of the chemicals found in everyday life that are inescapable. These include resveratrol and turmeric.

Check out the Your Health Guide podcast to learn more about the importance of detoxification and how a detox works.

The Cost of Organic…or Not Going Organic

Deciding whether to go organic or not (based on how much you can afford) may seem to be simply down to the price tag in front of you – but is it? According to Australian Organic[7] there’s more to it, as organic doesn’t cost the earth…quite literally. Certified organic farmers help protect our environment, reducing chemical run-off going into Australian waterways and coastal areas; helping our marine life and aquatic plants. Certified organic meat also has to be free range, and I mean really free range. These animals and birds are able to run on grass under the sun every day…not simply around a bewilderingly vast shed that does have an open door (so is technically ‘free-range’), but which they never actually go out of. So…no sow stalls, no caged chickens, no intensive feed lots, no routine antibiotic use, no electric prodders, no live exports – instead organic farmers focus on allowing their animals to carry out their natural social and physical functions with limited stocking rates (less crowding).

It’s a big topic, so simply know that when you choose to go organic it has a much bigger impact on the world you live in – not just on your health.

References

[1] Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ). Chemicals in food – maximum residue limits [Internet]. Canberra ACT; 2018 [Updated April 2018; cited 2018 Jun 27]. Available from: http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumer/chemicals/maxresidue/Pages/default.aspx.

[2] Gore AC, Chappell VA, Fenton SE, Flaws JA, Nadal A, Prins GS, Toppari J, Zoeller RT. Executive Summary to EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocr Rev. 2015 Dec;36(6):593-602. doi:10.1210/er.2015-1093.

[3] The National Association for Sustainable Agriculture, Australia (NASAA). What to look for in labelling. [Internet]. Stirling SA; 2016 [cited 2018 Jun 25]. Available from: https://www.nasaa.com.au/consumer-information/consumer-labelling.html.

[4] Krol W. Removal of trace pesticide residues from produce. [Internet]. New Haven [CT]: The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. 2012 [updated 2012 Jun 28; cited 2018 Jun 27]. Available from: http://www.ct.gov/caes/cwp/view.asp?a=2815&q=376676.

[5] Oates L, Cohen M, Braun L, Schembri A, Taskova R. Reduction in urinary organophosphate pesticide metabolites in adults after a week-long organic diet. Environ Res. 2014 Jul;132:105-11. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.03.021. Epub 2014 Apr 25. PubMed PMID: 24769399.

[6] Australian Organic. History of Australian organic. [Internet]. Brisbane QLD, 2018 [cited 2018 Jun 25]. Available from: http://austorganic.com/consumers/7-reasons-to-go-certified-organic/.

[7] Australian Organic. History of Australian organic. [Internet]. Brisbane QLD, 2018 [cited 2018 Jun 25]. Available from: http://austorganic.com/consumers/7-reasons-to-go-certified-organic/.

Leave a Comment